LULU

by Frank Wedekind

As Frank Wedekind turned 28 he was living in Paris, reading Nietzsche, and generally squandering his inheritance on various prostitutes, the details of which he recorded in his diary. Among these women was one named Rachel, who he met on July 5th, 1892, on which date he records his admiration for her “tragic apathy." "She is as wholesome as a peeled apple,” Wedekind writes, using an image that will appear in Act Two of his Lulu, “and artlessly ardent to a degree I have never experienced with any other woman.” The impression is evident.

Only a week later Wedekind writes, “go into the Champs Elysees, where I get an idea for a gruesome tragedy.” This hardly insignificant reference is flanked on one side by an allusion to a society party and on the other by the realization that Rachel had been concealing a child by another lover. Thus marks the origin of Lulu, a grotesque travesty set in a world that’s lost all moral footing: corrupt, diseased, hedonistic. A young woman whose name may or may not be Lulu stands at the center of the work, which chronicles her sexual/conjugal exploits and subsequent death at the hands of a man who may be Jack the Ripper (1). It is a play about a target of lust fighting against the men who objectify and manipulate her. But she is also worshiped for her beauty and the title of the original Lulu, Pandora’s Box, alludes to the goddess in her. Lulu is Pandora, the first woman, perfect, created as a titan’s wife and fated to unleash evil into the world. It is not an accident that one of her several aliases is Eve, another mythological woman with an original sin to bear. Eve’s ingestion of the apple, which prompts the awareness of her nakedness, begins a sexual awakening that biblically brands the woman as a dangerous other, a temptress. Lulu does not only inherit this lineage, she exemplifies it.

The fear of woman and the need to possess her is represented over and over again in each ensuing act, re-contextualized by each subsequently insufficient marriage within which Lulu is trapped. In our production, Lulu too is reconceived according to the sexual fantasies of her then-husband; not just her nickname, but also her clothing and even her hair is altered -- like a human Barbi doll. With this in mind, perhaps Lulu shouldn’t be branded as a play depicting the female struggle, but rather an allegory of the struggle between sex and society. This is certainly a theme common in Wedekind’s work, particularly in his Spring’s Awakening. But unlike that play which presents the tragedy of children raised in ignorance of their own bodies, Lulu is a play about a culture steeped in hypocrisy, and repressed desire, bound to expose itself in violent displays.

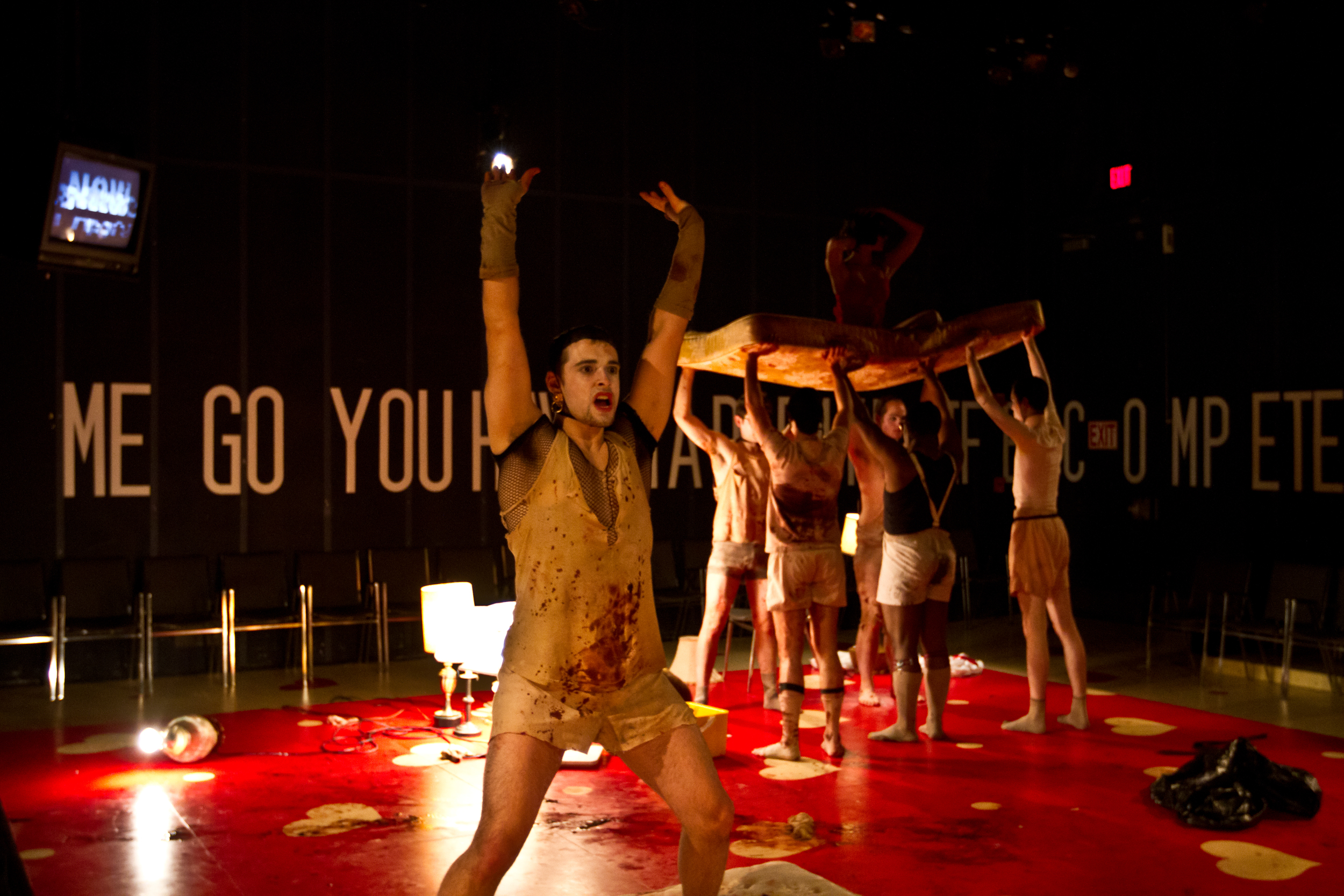

Our production begins with this exposure, pulsating techno and a striptease performed by all the men in Lulu’s life, after which they remain eternally in their underwear and stocking feet, similar to the johns depicted in Kohei Yoshiyuki's Park series. Inspired by Lucinda Devlin's Omega Suites, we transformed The Wells TV Studio at Carnegie Mellon into an oversized valentine in the round, implicating the audience by sheer proximity to the violence, the blood (conveniently located in large plastic tubs), and the sweat -- making transparent the unstated voyeurism of all theatrical performances. The hilariously murderous farce of act three, which discovers Lulu secreting away several lovers among several closets, was theatricalized by the gymnastic manipulation of mattresses. The ghosts of her dead husbands congregated over cards and cocktails in a waiting room with issues of Guns n’ Ammo. Transparent rain-coats barely concealed the fatal murder weapon. And once the lights came up, the stage was littered with debris: a ready made crime scene installation.

(1) Wedekind lived briefly in London at the height of Ripper fever. His distaste for the English city is made clear, however, not only in the last act of Lulu but also in his diary. He calls the English whores “frightful.”

Lulu was presented by the Carnegie Mellon School of Drama. The John Wells Television Studio, 2011. Choreography by Katie Rose McLaughlin O'Neil. Set design by Michael Simmons. Costume design by Peter Dolchas. Sound/Video design by Bart Cortright. Lighting design by Joe Israel. Featuring Ava Deluca-Verley, Abdiel Vivancos, Curtis Gillen, Josh Wilder, Dylan Putas, Corey Cott, Noah Plomgren, and Amanda Thorpe.